So much of the Pacific Northwest’s public lands and backcountry are located east of the Cascades. With the help of five outdoor enthusiasts, some who make their living out in the woods, we explore the diverse ways people work and play across the Inland Northwest’s vast wildlands. Their stories offer behind-the-scenes insights into the wild places we love, and we hope they will inspire you to get out and explore more of the region’s world-class mountains, forests, trails, and waterways. // (OTO)

As a kid in rural Iowa, Bart George had the same pastimes as many of his friends: hunting for deer and turkeys, roaming in the woods, fishing in the pond. Fascinated with animals, George would often bring them home to study, “rescuing” everything from raccoons to turtles. He had a makeshift menagerie filled with cages and terrariums—whatever he could put together “on a shoestring”—and creatures were always escaping.

Fast forward a few decades and that kid has grown up to become a wildlife biologist for the Kalispel Tribe, doing mostly field-based work in northeast Washington like surveying wildlife, doing grizzly bear and cougar research, and setting up game cameras. Fittingly, his work also requires—now, with significantly more skill and better equipment—capturing animals for the purposes of scientific study.

A lifelong hunter, George is also the co-chair of the Washington chapter of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers. “I’m lucky that I chose a career that sort of dovetails with hunting and fishing activities,” he says. Backcountry Hunters and Anglers has a mission that focuses heavily on the “backcountry” part, with a membership that’s passionate about conserving public lands: forests, lakes and streams, prairies, and mountains. As George puts it, it’s about “protecting big, connected landscapes. That’s what’s going to support the species that we care about now and into the future.”

“Hunters and anglers” is part of the group’s name, but it attracts outdoors lovers of all stripes: paddlers, hikers, mountain bikers, and likeminded others who agree with the message of conservation. The current political climate has given the group a membership boost, as concerned outdoorspeople respond to the threat of privatizing big pieces of national forest and other public land. In the last couple of years in particular, “we’ve really found an audience,” says George.

George has an affinity with the outdoors generally, spending time with his wife hiking and in other active pursuits. Hunting, though, has a unique, primal appeal. “It’s a very different thing when you go into the woods with the idea that you’re hunting,” he says. The pace changes. The awareness turns up. The focus is different. “You have to slow down, pay attention, listening to everything, watching—it’s a fun way to spend a day for sure.”

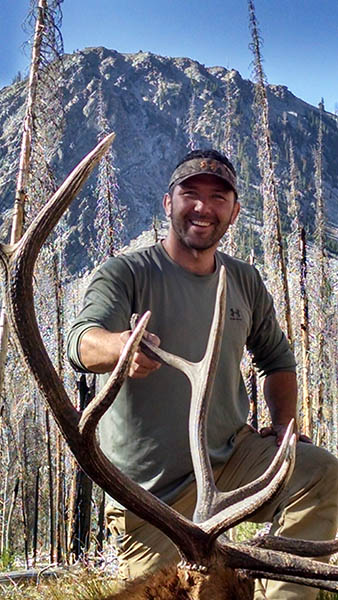

George finds that there are some common misconceptions about hunting, one being that success comes easily. Statistics vary by region and weapon type, but in Washington as few as one in 20 hunters may kill an elk, says George. For deer the odds are closer to one in four. Another misconception is that hunters are just looking for more trophies for their collections. That may be the case for some, but for George and others like him the appeal is more closely tied to a basic necessity: food. “We’re out there trying to get our year’s supply of meat,” he says. “My family enjoys it. It’s healthy, organic, good meat”—and local to boot. If he’s fortunate enough to get a deer or an elk, that’s what his family will be eating.

Hunting, as George describes it, is holistic. It’s not just about the kill, or having fresh, local game to eat, or time in the woods; it’s all of it coming together. “I think it’s more about the experience than the harvest or the kill,” he says.

George hunts regularly in Northeast Washington and in the panhandle of Idaho (he’s understandably loath to give away anything more specific than that), packing in gear to spend a week in the woods. “We’re almost always camping, getting as far away from the road or trailhead as we can,” he says of himself and his companions. Sometimes they haul gear in backpacks, sometimes they’ll use mules, sometimes they’ll bring it in on mountain bikes. Part of their ethos includes avoiding technology such as drones and ATVs that others may use as hunting tools. “It’s a backcountry experience free from technology,” he says.

Though he and his backcountry hunting buddies try to leave behind civilization to hunt, they sometimes do come across other people—and when that happens, it’s almost always a happy connection. “That’s one of the funny things,” he says. “I kind of joke about how we try to get away from people as far as we can when we’re hunting. But almost without exception, if we bump into someone in the backcountry, it’s someone we could be friends with. They’re generally likeminded folks.” //

[Feature photo: Matt Scott and Bart George packing out two bull elk in the Frank Church Wilderness Area. // Bart George]