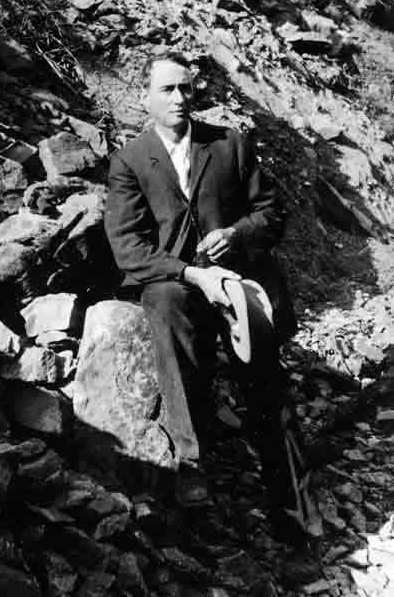

Forty-year-old Edward Crockett Pulaski—known as “Big Ed” because he was 6 feet, 4 inches tall—was much older than his fellow U.S. Forest Service colleagues when he was hired as an assistant ranger in the summer of 1908. The Forest Service had only been established three years prior by President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt and the first head of the Forest Service, Gifford Pinchot. Born in Ohio, Pulaski moved to the Inland Northwest when he was only 16 years old and in search of work during the gold rush in Murray, Idaho.

Pulaski, along with other rangers and hundreds of firefighters, toiled relentlessly during the summer of the Great Fires of 1910. Multiple wildfires ravaged the drought-stricken forests in the region. His actions during the “Big Blowup” (also called the Big Burn)—when hurricane-force winds inundated the region on Aug. 20-21 and merged the fires—is what made Pulaski a genuine American hero. The blowup’s epicenter included the Coeur d’Alene and St. Joe National Forests, what is now mapped as the “southern two-thirds of the Idaho Panhandle National Forests,” according to the U.S. Forest Service. Unable to escape the firestorm, more than 80 firefighters perished.

In Wallace, thousands of residents fled on trains summoned from Spokane to rescue them. In the forest near town, Pulaski and his firefighting crew of about 45 men were overcome by the firestorm. He led them to seek shelter in an old mineshaft tunnel. At the entrance he fought the fire with his bare hands and a wet blanket, as recounted by Pulaski in his first-person account, which was published as the winning entry in a Ranger Essay Contest years later. Flames seared his eyes and severely burned his hands and face. When panicked men tried to flee the tunnel, Pulaski threatened them at gunpoint so they’d stay. That night of Aug. 20, fire raged for five hours around the tunnel, and everyone was unconscious from smoke inhalation; five men would not survive that night.

When it was finally safe to leave, Pulaski, though now blinded, led them to the hospital in Wallace, where he would stay two months recovering from burns and pneumonia. Afterwards he advocated the Forest Service to pay for his crew’s hospital bills. Pulaski’s wife and daughter, Emma and Elsie, also survived the fire, having sought refuge on a rock pile of mine tailings, as Pulaski had told them to do if they needed to evacuate their home.

The following year, in 1911, in his blacksmith shop, Pulaski invented a re-design of a tool that’s now known simply as the “pulaski”—a two-bladed combo of ax and adze (grub hoe), used today by wildland firefighters.

Pulaski continued working as an assistant ranger for the Wallace district for the next 20 years. According to historian Stephen J. Pyne, in the ensuing years after the Great Fires, Pulaski oversaw recovery of the area—replanting seedlings, salvaging burned timber, and reconstructing trails and phone lines. He also tended to the graves of the fallen firefighters and advocated for memorial sites.

Today, the Great Burn Recommended Wilderness Area is 275,000 acres of roadless wilderness in the Lolo and Nez Perce/Clearwater National Forests straddling the Montana-Idaho border. First proposed to Congress by the U.S. Forest Service more than 40 years ago, the Great Burn Conservation Alliance continues advocacy of official wilderness protection.

Historic Great Burn Sites

- Pulaski Tunnel Trail and Pulaski Historic Site: 4 miles round-trip with interpretative signs to the tunnel overlook. Trailhead located off the road to Moon Pass, less than 10 minutes outside of Wallace.

- Ghost Cedars: Located near Avery, the Cedar Graveyardwetlands of the North Fork of the St. Joe River have large, standing dead cedars (called snags).

- Firefighter Memorials/Gravesites: (1) Nine Mile Cemetery, Wallace – final resting place for firefighters and townspeople who perished during the Great Burn; (2) Forest Cemetery, Coeur d’Alene – Ed and Emma Pulaski gravesites. (3) Woodlawn Cemetery, St. Maries –Firefighter memorial.

- See “Day Trip Guide to Historic Sites in Idaho and Montana” for more info.