By Matt Kinney and Tabitha Gregory

Abercrombie Mountain stands amid the mountains just shy of the Canadian border in northeast Washington. A popular trail to the summit switchbacks through dense forest and ascends through fields of wildflowers punctuated by silver snags. The mountain’s trail, natural beauty, and high elevation make it an appealing destination for hikers and mountain bikers, and its namesake’s history creates an intriguing web of connection with other Northwest landmarks.

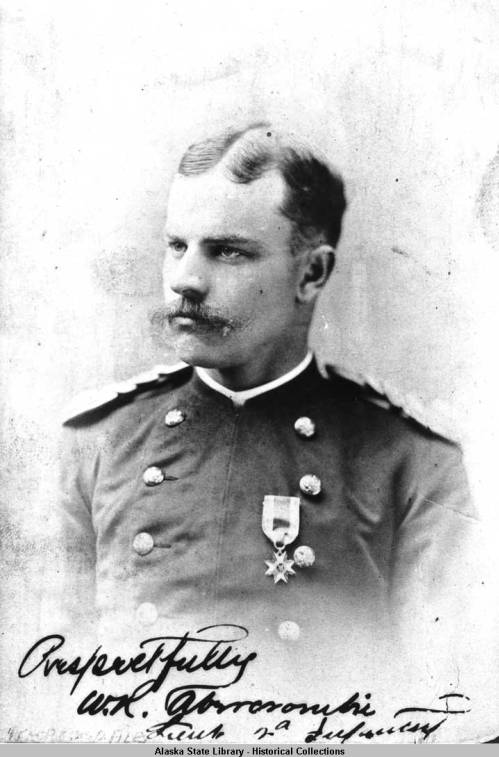

William Abercrombie, for whom the mountain is named, was raised in New York. In 1877, at the age of 19, he joined the Army and was assigned to Fort Colville, located near the present town of Colville, Wash. While there, he surveyed and mapped swaths of wildlands surrounding the Pend Oreille River, Priest River, Columbia River, Montana, and north to the 49th parallel—including the Abercrombie Mountain area.

Abercrombie’s experience exploring the Inland Northwest made him a strong candidate for more distant expeditions. So, in 1884, as Lieutenant Colonel, Abercrombie began leading missions to Alaska. He explored the massive Copper River three times, crossed the rugged Valdez Glacier, and established order in the chaotic gold rush-tent-city of Valdez.

One of his most notable Alaska projects was to locate, engineer, and construct an overland route to the interior gold fields through the Chugach Range. Today, this route is known as the Richardson Highway. In Alaska, there is an Abercrombie Peak, an Abercrombie Creek, and an Abercrombie State Park—all named for him.

Abercrombie returned intermittently to eastern Washington while serving in Alaska and eventually was promoted to Commander of Spokane’s Fort George Wright, which still stands today on the grounds of Spokane Falls Community College. Towering ponderosa pines rise along the grassy parade grounds, and pristine red brick buildings line the lanes. The Fort’s construction began in 1898, well after the so-called “Indian Wars,” but the namesake—George Wright—has become a modern-day symbol of the atrocities committed by the U.S. military against indigenous people. As a matter of fact, in the spring of 2021, Wright’s name was removed from the bordering roadway.

In 1910, Abercrombie retired and moved from the stately Post Commander’s House to a mansion on Spokane’s South Hill. His retirement house still stands today on a quiet street in the Cannon Addition, a plaque identifying it as the “Abercrombie House.” The home is grand with west-facing windows and a green lawn and landscaping. The original basalt rockwork of the foundation is still visible.

Each place that today bears Abercrombie’s name, in Alaska and in Washington, is beautiful and interesting in its own right. And the Abercrombie connection allows visitors to see some of the ways in which the region’s geography, geology, and history are drawn together.

Matt Kinney and Tabitha Gregory live in Spokane where they explore the Inland Northwest’s trails by foot, bike, and ski. Matt is author of “Alaska Backcountry Skiing: Valdez and Thompson Pass” and Tabitha is former director of the Valdez Museum and author of “Valdez Rises: One Town’s Struggle for Survival After the Great Alaska Earthquake.”