By Jean Arthur

Nearly 90 years ago the first rope tows were installed on slopes across the snowy places of the U.S. In 1937, the first rope tows in the West chugged into action at Snoqualmie Summit, Mount Rainier, and Mount Baker.

The Seattle Times writers opined in the Feb. 28, 1937 edition, “Skiers are not made by climbing hills. Skiers develop proficiency by coming downhill.” The article noted that at Mount Rainier, skiers can potentially ski 4,000 feet of vertical in a day. Of course, today, some lifts exceed 4,000 feet vertical and adept riders might reach 50,000 vertical per day. The lift-accessed record is nearly 65,000 feet skied in one day.

As ski clubs formed and ski hill managers built rope tows, farmers got into the action. Harold Termaat farmed near Kalispell, Mont., but in the winter, his fields were covered in snow, so from the late 1950s through 1968, he rigged the ropes.

Termaat once told me that, “I had two tows and two John Deeres going at the same time.” The rope for his homemade lifts ran around the tractor wheel. “We got 50 cents [a day] for the small hill and a dollar for the big hill. Parents said it was the cheapest babysitting they could find.”

Although not many are still rigged by tractors, a surprising number are still employed around the country. “We estimate that there are approximately 670 tow ropes in the U.S. today,” says Adrienne Saia Isaac, director of marketing and communications for the National Ski Areas Association. “As for historical tow ropes, we don’t have any exact record, but…the number was definitely in the thousands.”

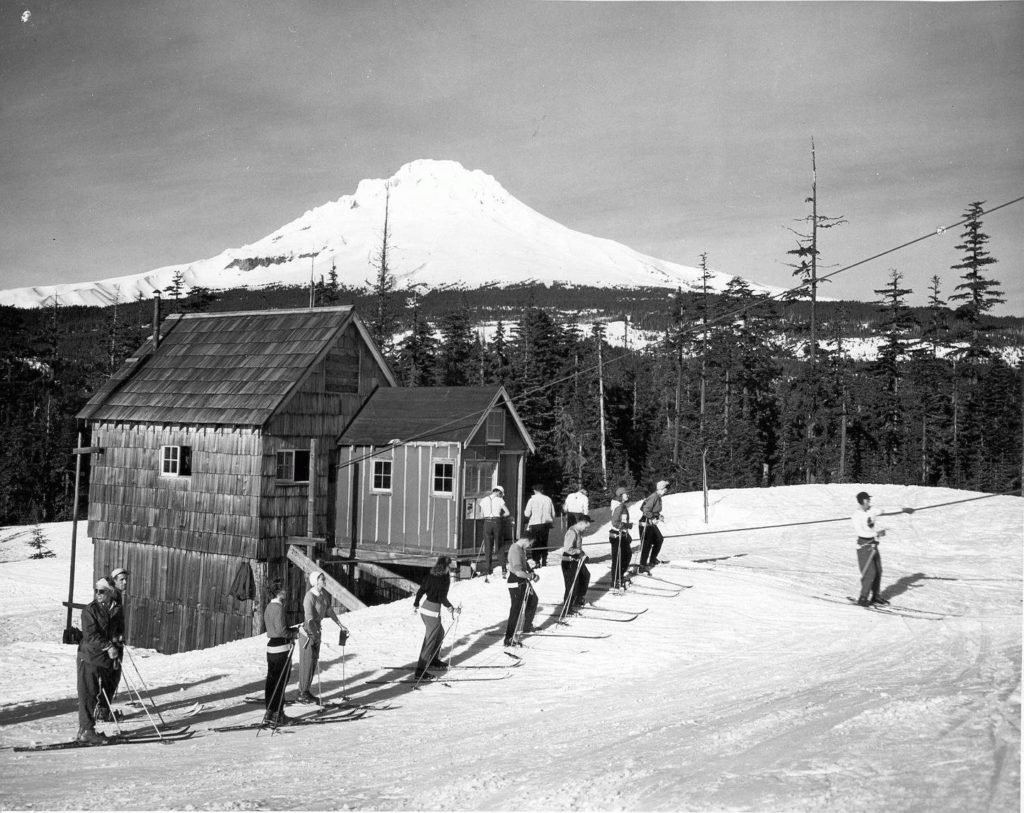

My earliest memory of rope-tow riding was at Mount Hood’s Multipor ski area, now called Mt. Hood Ski Bowl at Government Camp. The old tow wasn’t especially long, but it accessed a beginner slope full of other four and five year olds, outfitted in hand-me-down boots and skis, wool sweaters and long knit hats, which were dangerous—or so I found out.

One wintery day as my older brothers dashed off to the t-bar, I skied the 100-foot slope with other little kids. I loved my long stocking hat, knit by my mother, green and white and pink with a white puff ball of yarn at the end of the three-foot-long pointy cap. As I neared the top of the rope tow, my hat was pulled off, wrapped around the tow rope, and sent through the greasy mechanism before dropping like a dead raccoon. The next Saturday, a sign at the tow read “No long stocking caps allowed on rope tow. Tuck in all hair.”

On another snowy day at Multipor, my friends and I rode the rope tow once again. I had black leather mittens, which were neither waterproof nor warm, but we were having fun. Until, once again, the rope tow somehow snagged the metal hook on my left mitten. When I went to let go at the top of the tow track, I couldn’t. I was dangling from the moving rope by the mitten cuff and the metal hook. Luckily, the lift operator saw me, skis five feet in the air. He shut down the tow. My hand slipped from the mitten, and I crumpled in a pile. My dad thought it was time to learn to ride the t-bar, and that’s another story.

I sometimes visit ski hills with rope tows. Still, no long-knit hats for this skier.

This story originally appeared in the March 2020 print issue entitled “The Rope Tow” in the On the Mountain special section’s artifacts column.

Jean Arthur has worn out numerous pairs of mittens riding rope tows, t-bars, poma lifts, trams, trains—and the latest at Big Sky Resort—the eight-seater Ramcharger chairlift, the first of its kind in North America. She skis and writes from Bozeman.