Cover photo courtesy of Derrick Knowles

By Ammi Midstokke

Once, my friend Larry told me that if I want to be a good writer, I must learn to read poetry. But we all know Larry is crazy, and so after I stumbled through a few New Yorker poems like a kid trying to sprint through tires in gym class, I set them aside and declared myself an aficionado of complete (if not run-on) sentences.

Then I went to Oahu and I listened to some poems by the very souls who wrote them, and it was as though the broad gates to an unapologetic world of perspectives flung open and invited me in. I sat rapt and wrapped in their words as my head and heart filled with stories of birds, of battles, of battered ecologies and the oppressed, and the dead-and-dying languages, and I fell asleep that night with whispers of them all in my dreams.

I sipped, like hot tea, the poems of “Green Leaves” by Eric Paul Shaffer, stuck in one titled “Whales at Sunset.” Shaffer carried me through a sunset, the sound of waves, the distant viewing of whales—things written about as often as they have happened, but somehow individual, precious in their uniqueness. I am on the beach, I hear the waves, I see the whales. “Centuries ago, the sea seethed / with the play of whales. Now the ocean blackens with night,” Shaffer writes.

I feel the loss, the rage, the hopeless resignation to the truth that humanity is as humanity does and because I am reading a poem, I too am human. The only balm to this tragedy is the beauty we occasionally, accidentally, impermanently produce. But the animals and trees and oceans cannot read our poems.

Back in the Northwest, I see the world in a different kind of broken prose and pause. Each observation has a new depth and curiosity to it, as though perhaps we don’t need as much context to understand the complexity of a wondrous thing. It is spring and will become summer and I am watching nature in the punctuated, spaced lines of poetry.

It brings a childlike curiosity to my observation of flowers, the shades of green in different flora, and suddenly I am so careful, so careful to not tread on the yarrow or the lupine as I weave my way between the shade-crowded pines and find safe soil on which to step. In a world where we are losing tolerance for anything longer than a TikTok, poetry may save us from ourselves, guide our return to the senses and sensible.

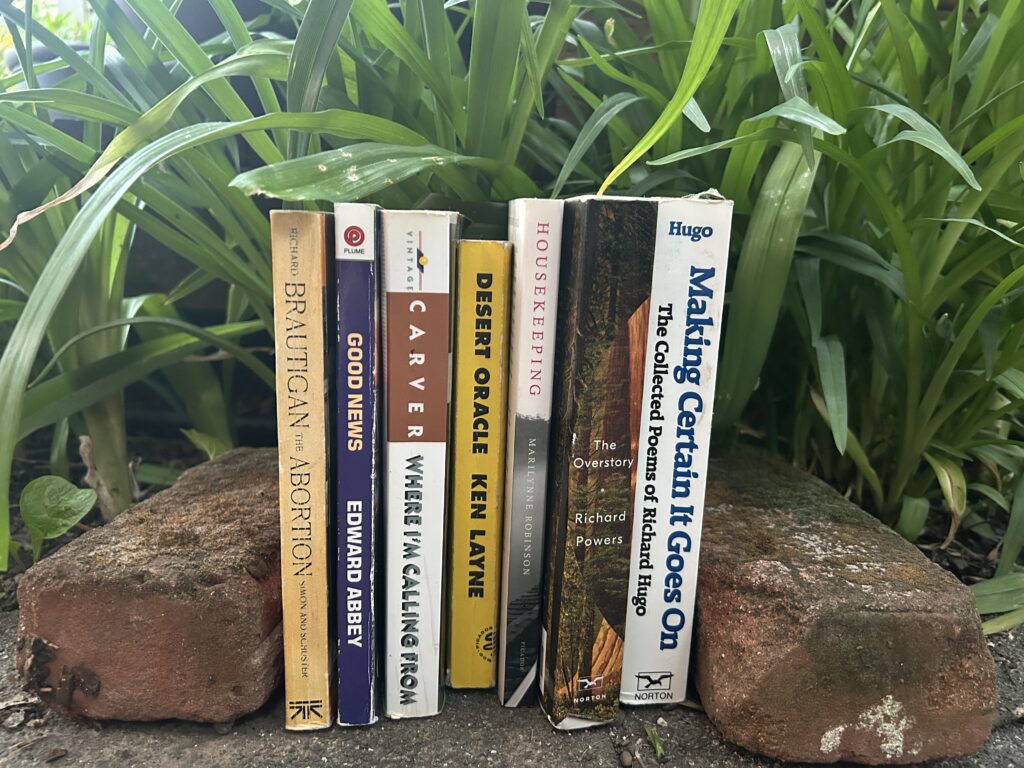

It is more forgiving than trying to drag my ass through “The Overstory” or “The Monkey Wrench Gang,” which I have only read because they are a social-literary rite of passage and cause to nod knowingly at parties with conservationists, but not because I particularly liked them.

Ah, but poetry! If you’ve ever met a poet, you know they are in a sophisticate class of their own, a group of people who love being misunderstood as much as they love being understood. The message they all share, the one imperative we learn—whether we understand the allusions or not—is to slow…the…eff…down…and pay attention.

If we were a world of poets, surely we’d find more commonalities than disagreements. We’d argue over comma scarcity perhaps, and the only harm that would come would be a forced reading of William McGonagall and overconsumption of herbal teas.

As for me, I’ll take another stab at it. (Reading, that is, for the true scourge of humanity would be proven should I ever try to write the stuff.) The poets of today are activist troubadours on pages, with messages so powerful we can only take them in tiny doses. It is a medicine in which we are of desperate need.

Ammi Midstokke will spend her summer seeking the poetry of the people, from the indigenous wise ones to the biologists, the broken hearted to the proud, from Frost to Vuong and beyond.