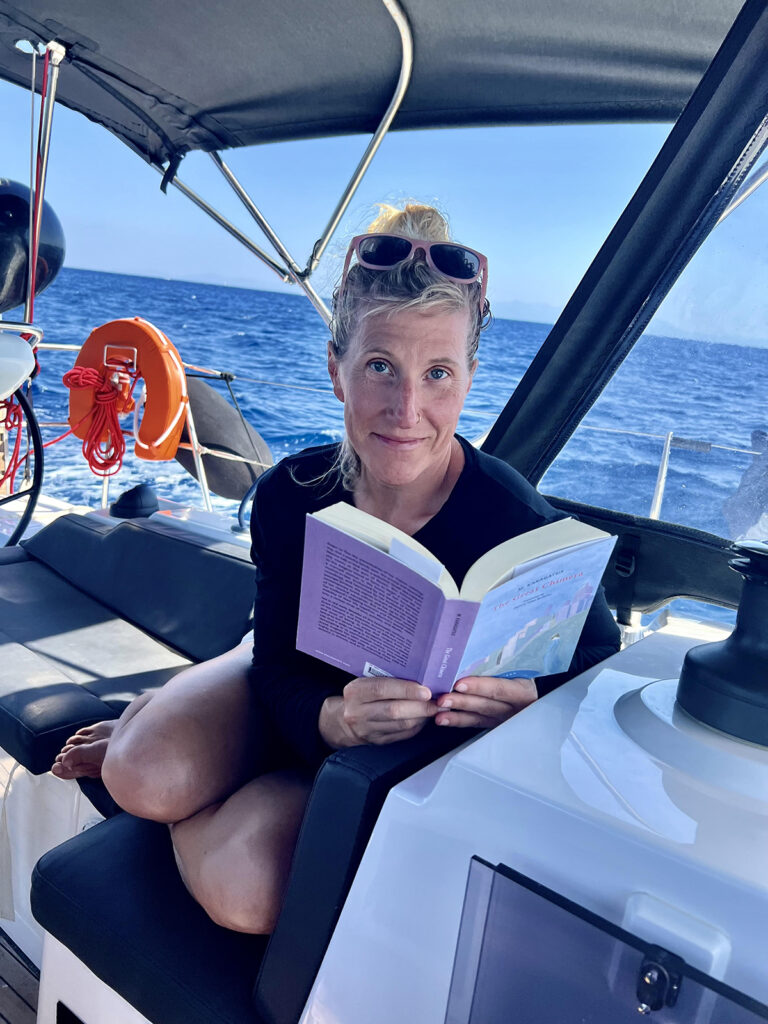

Cover photo courtesy Ammi Midstokke

The first time I was given a book written by Nikos Kazantzakis, I’d never heard of the nine-time Nobel nominee or even been to Greece. I did, however, have a Greek lover (as I recommend all people do at least one time in their life) who was trying to help me understand the great burden of being a Greek man.

In a country famous for producing the historically impactful (Plato, Socrates, Alexander the Great, El Greco, to name a few), the pressure to be the next prodigal son is apparently high. Also, olive harvesting is hard work, goats can climb trees, and you can yell at your priest if you apologize afterwards with an Ouzo. Or several.

Thus, I was gifted a copy of “Zorba the Greek,” followed by “The Last Temptation” and then “Report to Greco” as a sort of advanced coursework in understanding, as Zorba himself would say, “the whole catastrophe of life.” From a Greek’s perspective, that is.

The thing about perspective is that we’re really only granted our own unless we venture out to participate actively in that of the other. Even when we travel, we filter through our own lens as not just Americans (or whatever we are), but relatively privileged persons. We miss out on the nuances of a lived experience other than our own.

I believe everyone should read “Zorba,” because the wayward miner and lover of women and wine and, allegedly, hard work, brings with him a number of life’s wisdoms and charms. When he asks God for a sign of His existence, the almond trees blossom, as they always do. Until I smelled the trees in full bloom myself, I only vaguely grasped the cognitive experience. But being in a place offers a visceral one otherwise inaccessible, and breathing in the perfumed nectar of those blossoms added complexity and depth to my understanding that would have otherwise evaded me.

This is my pitch to read when you travel—to read the local writers, the naturalists of the area, those who have written of how a place was and is and may someday be. Those who tease from the language the unique beauty of a place, its changing dialects, its dying flora and evolving fauna. When you go to the Everglades, read Marjory Stonemason Douglas. If you find yourself in Poland, read Olga Tokarczuk so you can feel the chill of wind coming off the beech trees and over the frozen hills while you slip into the rhythm of a small village and a cynical vegan. In Turkey, Orhan Pamuk will serenade you on historical politics or the art of hand-digging a well in the native soils. Either way, the olives will taste better.

Read the naturalists when you’re in nature, read the stories of the Indigenous Peoples because you live on their land, read the poems of a linguist who tried to save a language (Frederic Mistral in France and Joy Harjo of the Muscagee Nation when you’re in Tulsa, though she writes from many places).

What I learned most from reading local literature was that the imperative to read from the places we visit and the places we live is rather a moral obligation. It is also how we can expand our perspectives beyond our otherwise solipsistic experience. It opens our hearts and senses to the overlooked, lifts veils we do not know exist, and ultimately deepens our understanding of each other.

How much we need that right now…

Ammi Midstokke’s adventures this year have led her to literature gold from Coeur d’Alene to Thessaloniki, from Spokane to Istanbul. Her late summer reading list includes Ben Goldfarb’s Crossings and a neglected copy of “The Monkey Wrench Gang.”