Sally Phillips is concerned. As one of Spokane’s longtime leading cycling advocates, as well as a board member for Spokefest—the Inland Northwest’s largest bicycle ride, held the second Sunday in September—Sally fears the event’s future is increasingly murky.

“Last year we were about to cancel the whole thing until the day before,” she says. “In fact, we’ve almost cancelled it two of the past three years because wildfire smoke made outdoor activity hazardous, and we don’t want families with kids riding in unhealthy air.”

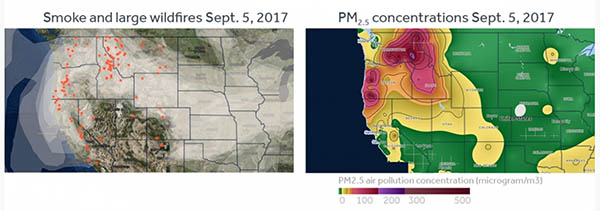

The cyclists weren’t alone. Throughout 2017’s summer and fall, football, soccer, and running practices were cancelled; hiking trips were called off; parks and tennis courts went quiet. Across the Northwest, ashes sometimes fluttered down from the ghostly pall like powder snow. The reason was clear to anyone who checked online fire maps: Spokane was surrounded by a thousand-mile-wide ring of flames stretching from Central BC to Napa Valley. “We never had to think about this before 2015,” says Phillips.

She’s right. Since the 1998 banning of field burning in Washington, the Spokane Regional Clean Air Agency rarely rated more than one day a year unhealthy due to wildfire smoke until 2012, when there were two. Then came 2015 with 13 such days; then 2017 with 16.

Is This the Smoky New Normal?

Science says this may well be the new normal, until it gets smokier still. Anthony Westerling, Professor of Environmental Engineering at University of California, Merced, has led teams of researchers tracking the growth of western wildfires over decades. Writing in The Conversation, he says, “It is a warming climate that is drying out western U.S. forests and leading to more, larger wildfires and a longer wildfire season.”

Westerling’s team finds that the area of burned forest in the Northwest—the hottest of the nation’s hot spots for wildfire growth—grew by 5,000 percent between 1973 and 2012 while Western fire seasons are now 84 days longer.

The rising tide of smoke has deep consequences. For one thing, airborne particulate pollution’s well-known link to heart disease and strokes. Also, a massive study published this July in “The Lancet” medical journal shows strong evidence that breathing particulates contributes to diabetes as well, accounting for fully 14 percent of diabetes cases.

Smoke is only part of the climate challenge. Spokane Riverkeeper Jerry White Jr. thinks more these days about drought and its impacts on fish habitat and river running. “Rafting the river provides a fantastic tourism draw for visitors to Spokane, and I’m always pleased to meet people from faraway places in the boats,” he says. “However, 2015 saw river flows drop so much by midsummer that downstream rapids like Bowl and Pitcher and the Devil’s Toenail became unrunnable, so the outfitters had to go to faraway rivers, and Spokane lost out on that business.” White says he expects more years like that ahead, with spring river volumes coming earlier and declining to low flows by the middle of summer.

“Those earlier drop-offs in flows also hurt trout, stranding trout fry before they can wash downstream,” says White. “And summer water temperatures often rise much too high for trout in places like the upper Spokane near the state line, where they are forced to move along the river in search of cool spots near springs or deep pools.”

And that heat is expected to grow. A study by Oregon State University’s PRISM Climate Group calculates that if emissions continue on present trend, by the year 2100 Spokane’s current 81-degree-average summers will become 93-degree-average summers like those of far southern Texas, with even more heat beyond.

In a region that takes special joy in outdoor pursuits, all this is as welcome as a turd in one’s Gatorade. What does it mean to face challenges like these with outdoor activities that are much of why we live here in the first place?

High Altitude Impacts

I discovered another possible example of climate change in mid-June, while climbing Mount Hood. Our team could not depart the Timberline Lodge parking lot at the usual 1:00 am; now, you leave two hours earlier because rock fall on the summit pitch becomes dangerous at sunrise rather than hours later, as before. Even in the traditional peak week of that popular mountain’s climbing season, in this good snow year, the standard Pearly Gates route had quickly melted into a rock-spitting bowling alley a full month before expected.

Meanwhile, Mount Hood’s famed summer skiing and snowboarding camps are closing earlier, especially in El Nino years like 2015, when Timberline’s August 2 closure was the earliest since the opening of the Palmer Lift forty years ago.

Up at Whistler, the venerable Camp of Champions declared bankruptcy last year due to climate change. Owner Ken Achenbach announced the closing in a sudden post on the camp’s website: “Simply put, it’s the effects of global warming. I wanted to give you [campers] an exceptional experience, and now I can’t. I haven’t slept in a week. After 28 years my dream is over.”

That was a shock, but Whistler is feeling the heat elsewhere as well. 25 years ago outdoor retailer REI shot its winter catalog photos in midsummer on a small glacier conveniently located at the top of the Whistler Village Gondola—a glacier that no longer exists. Now a bowl of bare rock, it’s merely one of Whistler’s multiple glacial casualties, along with Decker Glacier, which is now Decker Lake.

Still, every warming cloud has its silver lining. “For climbers climate change adds uncertainty,” says Matt Jeffries, president of The Mountaineers’ Spokane chapter. “At the same time, this may actually create opportunities and longer weather windows. The permit season in the Enchantments may last longer into the fall. Also, weather extremes bring surprises like last winter’s cold in interior Canada. We saw ice climbing routes last longer in the Canadian Rockies, starting early and going long on everything from Cranbrook up to Jasper. Then you see things like the retreat of the Athabasca Glacier, up along Canada’s Icefields Parkway. It has receded and dropped so much that the tour bus parking area recently had to be moved downslope to get close to the ice.“

Adaptation in the Great Outdoors

Adaptation has long been under way in snow sports; witness Mt. Spokane Ski and Snowboard Park’s protracted, controversial effort to expand chairlifts and runs to the mountain’s northwest side where snows last longer—a plan mirrored by similar projects at other Northwest ski areas.

Another game-changer for coping with warmer, less predictable weather is the worldwide turn towards snowmaking. After lagging the country in snowmaking for years, Northwest resorts are finally coming to terms with rising snowlines and the rising threat of snow droughts, even here where snow has always been abundant. Nearby hills like 49° North and Schweitzer now make snow to ensure adequate early-season coverage.

Meanwhile, in summer, many hikers, mountain bikers, and climbers now plan backcountry trips to skirt the late summer fire season. We think more about water sources and less about having campfires.

We should think more about bugs as well. In April the Centers for Disease Control reported that insect-borne diseases have tripled in the U.S. since 2004, thanks largely to “warmer weather” (climate change being a taboo term in Trump-era federal reports). The Northwest now sees bug-borne maladies once largely confined to the Southeast, like West Nile virus and Lyme disease, while other states now experience their first cases of the tropical staples: malaria, dengue, Chikungunya, Chagas disease, and Zika.

It might also be wise to reconsider the long-held dreams of owning a cabin getaway, as fire danger continues rising, with insurance rates sure to follow. We can’t wag fingers at Florida homeowners who rebuild beach homes after increasingly-strong hurricanes while we build houses ever farther into the Inland Northwest’s tinder-dry woods.

Most of all, we think about when it’s safe to breathe. North Idaho cross-country coach Erin Lydon sums it up: “My husband and I moved to Spokane from Chicago for outdoor activities, choosing this over Bozeman and Boulder, our other two finalist options. But clean summer air is important to us. Why live here if you can’t go outside during the year’s best weather?”

Lydon trains 33 cross-country runners aged 7-16 from Spokane and Kootenai counties for the USA Junior Olympics, held each December. That puts their peak training period square in the middle of fire season.

“August is our key training month, just prior to September’s race season start, yet it has the worst air quality,” she says. “I don’t recall ever canceling a practice for air pollution before we had to cancel five in August 2015, then we cancelled six in August 2017. Now we go by the EPA’s Airnow app. Any reading above 120 is a definite cancellation, and 110 is probable.”

What’s Next?

It’s very literally a new world, with a coming climate probably unlike any seen since the dawn of humanity. For decades, new climate science findings have consistently trended towards more alarming conclusions, which is almost certain to continue as we learn more about climate feedbacks and knock-on effects.

We who live and love the Northwest outdoor life are in a good position to lead our region towards the cleaner future we need, to preserve what we enjoy and to pass it along for coming generations to enjoy as well. It is neither hard nor expensive to set a better example and to get involved. // (David Camp)

David Camp is owner of Camp Creative, the sales & marketing director for Northwest Renewables, and a board member for 350 Spokane. This is his first article for Out There.

Adaptation VS Prevention

As valuable as adaptation is, we all face a more vexing question as well: what can we do to avoid making the problem worse ourselves? After all, transportation is our region’s top source of greenhouse gas emissions, and outdoor sports enthusiasts are chronic offenders, driving gas-guzzling, gear-hauling rigs to far-flung destinations. We can do better, and without too much trouble. Every nation on Earth has officially agreed to decarbonize, so let’s do our part. Here are major ways you can make a personal difference:

- Transportation: Never buy another gas or diesel vehicle again; go electric, plug-in hybrid or car-free. In town, help push for transit and bike infrastructure.

- Home: Go solar, get rid of gas, and think of upgrading with heat pumps, efficient windows, and appliances.

- Diet: Cut red meat and dairy, which have enormous carbon costs, and eat at least a few vegetarian meals per week.

- Savings: Move your money from S&P Index funds to fossil-free funds like those from SPDRs, which have outperformed for years as fossil fuels lose value.

- Vacations: Stop flying and explore closer to home.

- Volunteering: Join climate-conscious groups—especially strong, local ones like 350 Spokane.

- Vote: Support political progress such as Washington State Initiative 1631’s carbon fee (on this November’s ballot), and the City of Spokane’s push towards fossil-free electricity.

- Some Good News: Except for volunteering, all of these measures will save or make you money. They’ll also help Spokane compete for talent in a world where highly educated, highly mobile young people value clean energy, healthy eating, and denser living. //

[Feature photo: Courtesy of Schweitzer Mountain Resort.]