Last autumn, I was winding my way toward a ridge in the Salmo-Priest Wilderness when a shadow cast briefly over my head once, twice, then thrice. The trees were thinning out as I climbed higher, but whatever was flying about was taking a pass, then settling safely in the camouflage of those towering, gnarled conifers.

I heard nothing, no beating of wings of warning of other birds, just that soft sound wind makes when you’ve climbed beyond the tree line and the wind is heard from below rather than above. After the third shadow-casting, I stopped to wait for friends and watch for the curious but clandestine fowl.

Within moments, an enormous owl appeared in the blue sky, suspended between treetops, then swooping in large circles overhead. I didn’t know what kind of owl, because I’m embarrassingly unfamiliar with the native inhabitants of most places I go. But one doesn’t see an owl in broad daylight without assigning it some kind of mythical significance or anthropomorphized relationship.

What was this owl trying to tell me? Was it symbolic of something? Do white women of European decent and urban birth have spirit animals?

I had no answers, though I assumed the latter was, “Yes, multiple domesticated cats.”

I didn’t even know why an owl would be out in broad daylight, though I was fairly certain the thing was getting a good look at me. Or maybe riding the wind? I rarely to never see owls when I’m about, but then again, I’m always looking down. And owls are incredibly good at hiding, I have since learned.

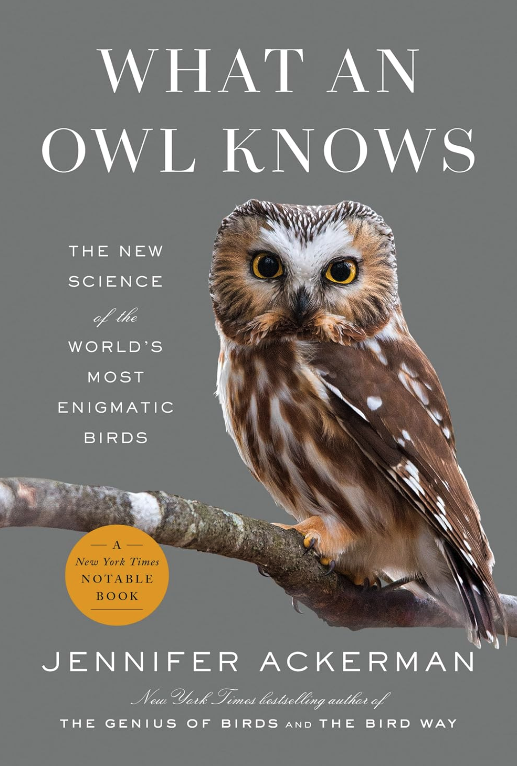

They are also playful and territorial and have been known to sink their talons deep into the skulls of runners and hikers and researchers on many occasions. I learned this and much more by greedily reading Jennifer Ackerman’s new book “What an Owl Knows.” That being said, I also learned much about people who study owls and one might argue they are equally, if not more, fascinating.

And owls are definitely fascinating. They are also vicious killers. They even eat other birds! They fly essentially silent, having evolved wings with particular feather architecture. Their hearing is so acute, scientists suspect it is connected to the visual part of their brain allowing them to “see” what they hear in the dark of the night. And they hear everything. A mouse walking across leaves is an easy target.

The thing about owls and so many of the creatures of the forest is that we often underestimate their ubiquitousness. They are everywhere—or at least everywhere we haven’t decimated their habitat. Some owls love to nest in tree snarls. Some love the top of a broken-off trunk. Some nest in the ground. All of them appear particular about their needs for breeding. Yet most of us are unaware of their presence, and in my case, just about everything else about owls.

There is a way our consumption of nature as recreation fosters a kind of obliviousness to it. We rally on our mountain bikes and take pictures for our Instagram. We log miles of trail and tell harrowing tails of epic adventure, but are we really paying attention to what we are witnessing?

After consuming much owl literature, I worriedly told my husband to stop cleaning up the snarled trees on our property. “We have to check them for nests first!” I pleaded, pointing out a broken-off ponderosa. “That is a perfect owl nest right there!”

It is only with a deeper understanding of nature that we can contribute to the preservation of it. We can read books, of course, but we can also just pause to observe the wonders when we find ourselves within it. Maybe you’ll even see the owl watching you.

Ammi Midstokke is searching her property for owl sign this spring and hoping to find a few bird condominiums in her dead standing pines. Next issue, she’ll be dispatching from the shores of the Aegean Sea or the summit of Mount Olympus.