My roots in the Crown of the Continent go as deep as my first wobbly steps on Earth. My folks came to the heart of the Crown with hope for a better life for themselves and their children. A handful of photos of the bob Marshall Wilderness in a 1985 issue of National Geographic sparked their migration. They packed up their old white station wagon and two infants to leave behind the city and its traffic, crime, and air pollution, and to embrace a new life of fresh air and fresh starts, settling in the rural northwestern corner of Montana.

My early years were full of huckleberry-stained hands, clothes sooty from picking morel mushrooms in forest fire burns, and the lingering smell of trout that clung to me after family fishing trips. In middle school I rode my bike beyond the edge of town to explore the woods and creeks flowing out of the Whitefish Range. I wandered looking for animals, fishing, and trying to live off the land in poorly constructed shelters that barely kept my skinny frame from hypothermia. I learned about plants and made tea from birch, mint, and spruce; I collected saskatoons, rose hips, and cattails for food. My awareness of humanity’s connection to the land grew in those creek bottoms and deep forests.

I still remember pressing my seven-year-old nose against the cold glass of my parent’s station wagon window, enchanted by the snowy peaks of the mountain ranges that form the Crown of the Continent. I tried to imagine what it was like up there, guessing that people couldn’t visit that rugged country. I didn’t know then that I would arrange my schedule in high school and college so I could spend as many days as possible in the Crown’s mountains. I laugh now, looking back at those trips. I often went alone and always inadequately prepared – camping for days with plastic bread bags inside of sneakers for snow boots, layers of heavy cotton-flannel shirts, and leaky one-man tent.

Those early forays into the mountains provided the first inspiration for the images in this book.

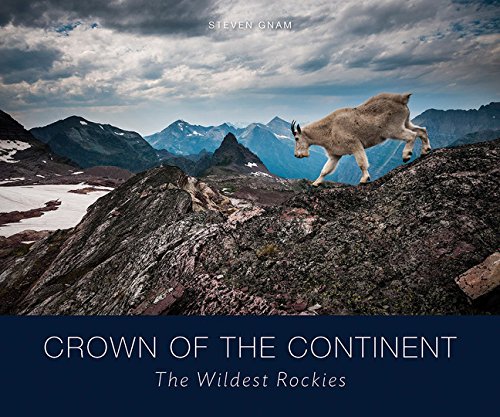

The Crown of the Continent – the expanse of the Rocky Mountains stretching roughly from Missoula, Montana, to Banff, Alberta – is unique in the world. From the convergence of the climates of the Pacific Northwest, Rocky Mountains, Arctic, and northern Great Plains springs up a colorful spectrum of plants and animals. In the Crown, the full suite of creatures that lived here alongside the region’s earliest human inhabitants still make their home in these mountains and valleys. Nowhere else on this continent, and very few places in the world, is such wilderness intact alongside modern society.

People live here to be close to the land; the land in return is what provides people’s living, as residents host visitors, harvest sustainable forest products, and care for the wilderness. The land also shapes the culture of the Crown’s communities. Climbing a peak, encountering a bear, and picking huckleberries all strengthen the bonds between place, self, and community, forming stories and memories. Experiencing strong, graceful creatures and intact landscapes rubs off a bit and enriches the beholder.

The blessings of the land are not just for its residents. Every year millions of people from around the world visit the Crown to escape the bustle of cities and to experience nature in its wildest form – to catch a glimpse of a grizzly bear or a wolverine, to hike in solitude, or to float a pristine river. These visitors come to experience something they can’t at home: the earth and its communities, whole and healthy.

The Crown of the Continent remains intact because a handful of people saw its natural resources and its beauty as something that should stay untouched for generations. In defiant acts of self-restraint, they chose to forgo the short-term rewards of using the land as however they saw fit and instead laid the groundwork for the long-term rewards we enjoy now: wide-open space, abundant wildlife, clean water. But these early visionaries who left a network of wildlands couldn’t anticipate the scale of growth and development that would come. Nor could they foresee that the protected islands of parks and wilderness would not be big enough by themselves for viable populations of wolverines and grizzlies, wolves, harlequin ducks, and eagles, in the long run. These creatures need more than island preserves – they need corridors and routes from Yellowstone all the way north to the Canadian Yukon. These connected lands offer space for wildlife to travel and mix with others of their kind, to roam in search of food, and to migrate in response to the changes that climate and time bring. (Braided River, 2014, www.wildestrockies.org). //

Editor’s Note: This beautiful book highlights one of the most wild, rugged, and relatively intact landscapes in North America. With stunning, artistic photography and authentic stories of the diverse people and wildlife that share the Crown of the Continent region of the Northern Rockies, it conveys a critical conservation message without getting bogged down in the overly preachy politics that often plague modern-day conservation narratives. Conversely, thumbing through the pages of this book left me energized and inspired, itching to see the massive mountains that form the continental divide take shape in my windshield on a drive north towards Whitefish, and to set out on a long walk into this vast, true wilderness only a few hours east of Spokane. Gnam’s passion for this place is palpable, and I highly recommend his book to anyone with a fondness for this rugged region of the Rockies. //