Who remembers that feeling, when you were young(er), and all signs pointed to the likelihood of living forever? There was always a new challenge to accept. The time to play was always there, and the ability to at least attempt was never in question.

Well, that’s only partially true, folks. Life is a timed event.

Let me provide some perspective on my own journey with mortality. I promise this has a reasonably happy ending.

In February of this year, I woke up with a strange feeling in my chest. The best way to describe it would be the sensation of a beginning percussion class full of tiny seven year olds attempting a jazz beat on my heart. My resting pulse, usually below 60 BPM, was as consistent as spring weather in the Northwest. All over the place. I was tired. I couldn’t climb a flight of stairs without getting winded.

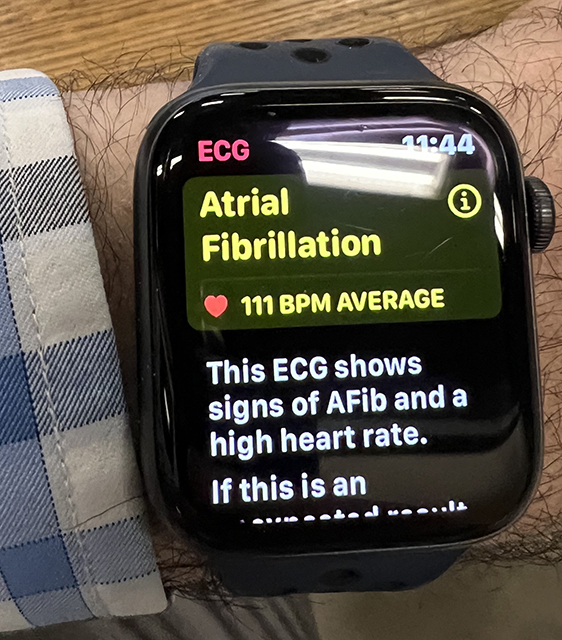

So I went about my days, until my Apple Watch told me I was in trouble. The device I associated with texts and changing the song was now telling me I needed to get to the ER, STAT.

Let’s just say that Kareem Abdul Jabbar and I now have something in common. Atrial Fibrillation is defined as an irregular and, at times, rapid heart rate that sets the top chambers of the heart (atria) and the bottom (ventricles) into a tempo that basically resembles the sound and feel of those moments when two cars blasting their stereos come to the same stoplight. The atria are cranking the syncopated jazz while the ventricles are sticking to mellow soft rock. It also, all joking aside, puts the likelihood of stroke about five times higher. Medications that thin the blood, limit the heart’s maximum rate, and a new friend in the form of a Cardiologist were now a regular part of my life.

This wasn’t fair. I have been a cyclist since the time of LeMond. Since the time of pedals with toe straps and leather helmets. I’ve taken reasonably good care of my body. I’ve been fit my entire adult life. Well, fit enough. To tell me I couldn’t potentially ride my bike is the equivalent of telling Santa Claus he can’t deliver presents. It is what defines me, and I was staring down the prospect of a house full of bicycles, a podcast and business about bicycles, and drawers of lycra all being useless paper weights.

So, after a few weeks of sulking around and waiting for a proper doctor’s appointment, I decided to speak with some people who know what they’re talking about. Lennard Zinn is an accomplished bicycle builder, mechanic, and author of “The Haywire Heart,” a book that discusses cardiac issues that can develop in endurance athletes. The good news is that it isn’t overly common. The bad news is that, according to Zinn, the research is just beginning to present itself. Athletes who began endurance sports in the 1970s, about the time of the original running boom, who have been pushing their cardiac muscles to their limits since the time of disco, are now beginning to experience heart failure issues.

Think about it this way: Zinn described it using the skin on the back of the hand. As one ages, the skin on the back of the hand becomes thinner and less flexible. Over 40? Try it right now. Notice that the skin is not as pliable as it was in your 20s. That process is happening all over your body. Continuing to ask for that same kind of blood volume in your 50s, asking the heart to enlarge as it would in your 20s, when it is no longer as flexible as it was, leads to what Zinn refers to as “micro tears in the myocardium.” When those micro tears heal, they cause scar tissue, which then can cause disruptions in the electrical signals in the heart.

I had a “wonky” heart, as the kids would say, because I chose to push myself for multiple decades.

The good news is there were, and are, options. The first, a glorified reset of the heart called a cardioversion, is simply applying an electrical shock to the heart to allow it to find its original rhythm, like when an IT worker tells you to turn your computer off and on again. While for many this is the only step required, mine only lasted about two weeks. The second was a bit more of a “surgical” procedure called an ablation, where the electrical signals causing the AFib are actually, well, destroyed, but in a good way. It sounds nasty, but was a procedure that only took about three to five hours in a hospital (some stay overnight). That happened May 1 for me.

I’m a very lucky person. I’ve been able to return to the sport that I love, and ride and race against my friends, and, most importantly, my son. What would I have done if that hadn’t been the case? I’d have continued. I’d have purchased an e-bike to still feel the wind in my face. I’d have supported my fellow cyclists.

I’ve learned to listen to my body. I’ve learned to check my watch for features other than skipping songs by Steve Miller. I’ve learned that regular doctor visits are a good call, even when nothing is wrong. I’ve learned that one can be a cyclist even though they don’t necessarily ride a bike. I’ve learned to get outside as often as possible, because as I stated earlier, life is a timed event, and fortunately my clock is still ticking along at or around 60 BPM.

Patrick Bulger has been an active and competitive cyclist for decades. He is also the host and creator of The Packfiller Podcast, a weekly show featuring the world of road, mountain, and gravel cycling.