Paddling a river through any desert area seems a contradiction, at first. In the arid middle of Washington State, the Columbia River churns past sun-bleached sage and grasses, jackrabbits and rattlesnakes, and, in one special stretch, an abandoned nuclear reactor.

Northwest of Richland, the Hanford Reach National Monument includes the bones of the Hanford Site, a government area used to develop nuclear materials for the Manhattan Project during World War II. The secret project required a large security buffer of land, off-limits to the public. As scientists cooked up plutonium, native flora and fauna crept back onto the land, which had recently been home to orchards, farmland, and a few small towns. After the war, cleanup began, and the isolation continued. A land untouched by development or agriculture since 1943, the monument area is now home to a beautiful desert ecosystem.

The nuclear reactors might be the showiest features of the area, but there are unique geological points and historical remnants as well. The monument is named, after all, for the Hanford Reach, the last non-tidal free flowing section of the Columbia River. Towering around the river’s curvature are the White Bluffs, hillsides created by giant whirlpools when water backed up from the Great Missoula Floods. There is glacial erratic, large rocks from other areas that were carried in on ice rafts. Zoom out, and you’ll notice giant ripples and gravel bars, impressions from turbulent waters that raged and then ebbed. Tucked in the soil are more unlikely finds—the White Bluffs have produced fossils of mammals from the Miocene Era, like rhinoceros, camel, and mastodon.

Due to its unique geography, protected land, and national history, the Hanford Reach National Monument was the first of eight such monuments administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. National Monuments are similar to National Parks, with the reason for preservation setting them apart—National Parks are protected for scenic value and recreation, whereas National Monuments must also have a national historic significance. National Monuments are not buildings, though many contain protected historic structures, like the plutonium reactors at Hanford. The land for a National Monument must already be owned by the federal government—clearly the case at Hanford—and can only be deemed a National Monument by a U.S. President, under authority of the Antiquities Act of 1906. (National Parks, on the other hand, can be created through legislation passed by Congress). The Hanford Reach National Monument was established by Bill Clinton in 2000. At the time of this writing, there are 158 National Monuments in our country.

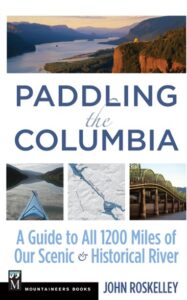

From a present-day recreation standpoint, the Hanford Reach National Monument is a great area for a paddler. John Roskelley, author of Paddling the Columbia: A Guide to All 1,200 Miles of Our Scenic & Historic River, has led multiple paddling tours along the Hanford Reach. He loves the cool, clear, free-flowing water of the area.

“The Columbia River has some of the best, most diverse paddling anywhere in the country, and the Hanford Reach is the iconic stretch along the river,” says Roskelley. “[It has] America’s nuclear history visible along the shorelines, shrub-steppe habitat and wildflowers that have never seen a plow, and a variety of wildlife and birds.”